Vernacular architecture in Hong Kong originated as a series of small, coastal settlements—simple, village-like communities that reflected the city's early identity as a fishing hub. These seaside villages were typically composed of low-rise, timber-framed houses clustered around temples, forming tight-knit communities closely tied to the rhythms of the water.

One notable example is Tai Hang, among the earlier settlements established by the Hakka people in Hong Kong. Originally located along a water channel that flowed from the nearby mountains to the sea, the area was once a vital washing site for villagers—hence its name, which literally means "Big Drainage." Before extensive land reclamation, Tai Hang sat quite close to the shoreline. Today, it lies nearly 700 meters inland.

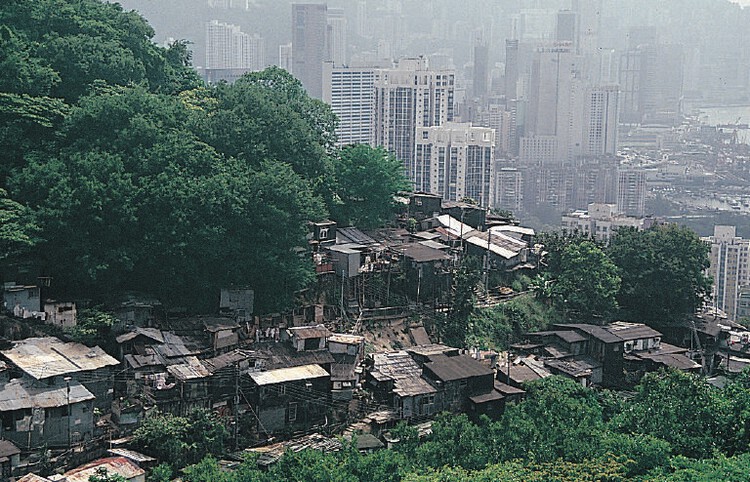

Historically, Hong Kong's vernacular architecture developed organically around waterways, often through informal or squatter settlements. In Tai Hang, Hakka villagers constructed modest wooden homes along the riverbanks, forming one of the region's earlier rural enclaves. While most of these vernacular landscapes have since been absorbed into the urban grid, a few structures from the earlier days have survived—preserved or adaptively reused, thanks to the neighborhood's distinct heritage and location.

Related Article

The Windows of Venice: How History Inspired Modernity

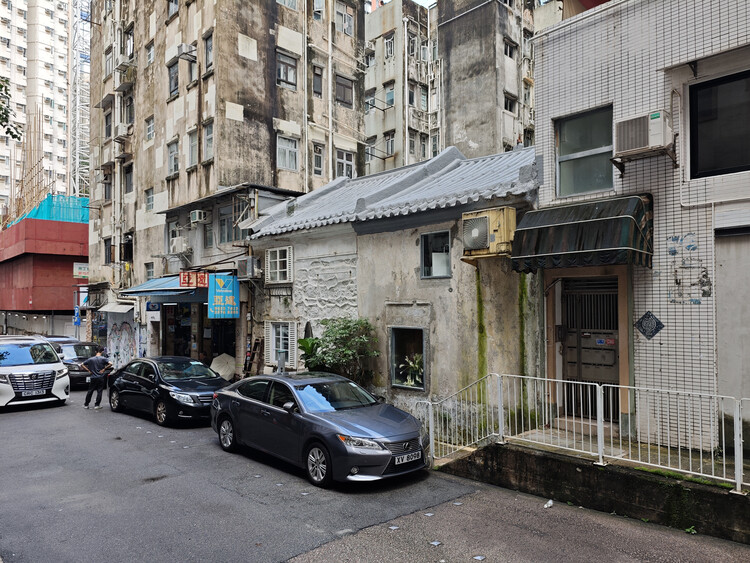

What makes Tai Hang particularly fascinating today is the coexistence of these traditional, low-rise forms—marked by sloped roofs and clay tiles—alongside pencil-thin residential towers and dense, contemporary architecture. Just a 10-minute walk away lies Causeway Bay, one of Hong Kong's most urbanized commercial districts, filled with high-rises, malls, and mass transit developments. Within this juxtaposition, Tai Hang offers a rare architectural dialogue between the historical seaside vernacular and the modern metropolis—a living pocket of cultural continuity embedded within a rapidly vertical cityscape.

Small-Scale, Big Impact: The Enduring Relevance of Vernacular Urbanism

Although Tai Hang was transformed from a rural village into a more structured urban grid in the 1890s, many of its buildings continue to reflect their vernacular roots—low-rise, low-density structures with sloped tile roofs. Over time, the neighborhood evolved into a vibrant mix of residential and commercial uses, yet it has remarkably preserved its village-like atmosphere. Even today, Tai Hang offers an impressively self-sufficient microcosm within Hong Kong: one can find everything from garages, hardware stores, laundromats, and stationery shops to veterinary clinics, doctors' offices, hair salons, tattoo studios, cafés, dai pai dongs, and bars. This richly mixed-use environment, paired with its pedestrian-friendly scale, is a rare continuity of Hong Kong's diverse way of life within its limited, approximately 300m x 200m area.

In stark contrast stands its immediate neighbor—Causeway Bay. While it, too, is walkable, it embodies a different kind of urbanism. Human activity in Causeway Bay is largely funneled through massive, air-conditioned shopping malls that prioritize consumption but offer little spatial or social diversity. Street-level engagement is often minimal. Pedestrians may encounter a succession of indistinguishable storefronts or, worse, walk uninterrupted for minutes along a blank mall façade. Meanwhile, vehicular traffic dominates the roadways—cars move faster, and pedestrians are hurried along, often honked at for lingering too long outside the flow.

By comparison, Tai Hang's streets still resemble a village in spirit—shared by pedestrians and cars alike, inviting slow strolls and spontaneous interactions. While some may argue that vernacular structures are inefficient, outdated, or economically underutilized, their continued presence sustains a form of urban life that is both culturally rich and human-scaled. Amid Hong Kong's vertical growth and the pursuit of economic intensity, Tai Hang offers a reminder of a slower, more authentic rhythm of city life.

Even within Tai Hang, however, redevelopment is gradually encroaching. New pencil towers are rising, often replacing multiple low-rise buildings with singular, vertical blocks that offer little to the street beyond a sleek, opaque façade. As this transformation continues, it's worth asking: can we learn from the pedestrian-friendly, socially vibrant qualities of Hong Kong's vernacular past? Can these qualities coexist with, or even inform, the city's future development? In the face of ever-taller skyscrapers and globalized retail landscapes, what kind of urbanism truly reflects the soul of Hong Kong—and what kind of city do we want to inherit?

Rethinking the Urban Fabric through Temples, Traditions, and Temporary Streets

Some of the most remarkable examples of vernacular architecture that remain in Tai Hang include Lin Fa Kung (Lin Fa Temple), a temple originally rebuilt in the 1860s and preserved to this day. Nearby, a handful of traditional residential-commercial buildings have been sensitively and adaptively reused—now home to contemporary galleries, pop-up shops, cafés, hair salons, and more. These quiet transformations offer a compelling glimpse into the enduring cultural relevance and flexibility of vernacular architecture, demonstrating how heritage spaces can continue to enrich urban life in meaningful, engaging, and evolving ways.

Lin Fa Kung, dedicated to Guanyin, the goddess of mercy, has been declared a monument of Hong Kong, receiving the highest level of legal protection. One of the temple's most remarkable architectural gestures is its anchoring around a natural boulder, which dramatically protrudes into the temple's interior. The reason for this siting remains uncertain, but its presence reflects an earlier, more site-sensitive mode of building—one that absorbed and responded to natural conditions, rather than reshaping them to fit a predetermined plan. In an era increasingly dominated by standardized, prefabricated systems—where sites are often leveled and molded to fit the system rather than the other way around—it prompts an important question: What are we losing when architecture no longer engages in dialogue with landscape and ecology?

Another enduring form of vernacular spatial practice in Tai Hang takes the shape of a collective community ritual: the Tai Hang Fire Dragon Dance, performed each year during the Mid-Autumn Festival and now recognized as a National Intangible Cultural Heritage. The dance, which involves a 67-meter-long dragon stuffed with burning incense, requires intensive spatial coordination. In the days leading up to the event, the dragon is assembled with the help of neighbors and volunteers; during the nights of performance, the streets of Tai Hang are cleared of cars and transformed into a pedestrian-only space. The event becomes a temporary reorganization of the contemporary village—where families, friends, and shop owners come together in celebration, activating the urban fabric through movement, sound, and ritual.

Though specific to its historical and cultural context, the Fire Dragon Dance offers powerful lessons in spatial adaptability and collective authorship. It reflects a vernacular approach to placemaking—improvised, responsive, and rooted in the rhythms of everyday life. As Hong Kong continues to densify—with deep foundations, sealed glass towers, and air-conditioned interiors increasingly dominating the skyline—one wonders: can such community-based spatial knowledge re-emerge as an antidote to the city's more monolithic urbanism? Might the presence of these cultural and architectural practices not only be preserved but reintroduced as vital ingredients in shaping a more humane, participatory future?

Growth with Memory: Rethinking Development Through Vernacular Values

The presence of Tai Hang within the broader context of Causeway Bay and Hong Kong Island mirrors the role of Lin Fa Temple within Tai Hang itself—modest in scale, yet rich in meaning. While it is understandable—and arguably necessary—that cities pursue economic growth through advancements in finance, architectural technology, engineering, and computing, these developments need not come at the cost of cultural and spatial diversity. Just as Lin Fa Temple and the Fire Dragon Dance quietly anchor the identity of Tai Hang, future urban development can benefit from preserving vernacular structures and supporting community-led initiatives, however small. These seemingly minor cultural touchpoints are often what foster meaningful human interaction—something vernacular architecture has long excelled at.

Can cities continue to grow while still maintaining a sense of balance—one that preserves cultural memory, encourages inclusivity, and resists commercial homogeneity? Rather than allowing entire neighborhoods to be overwritten by transit-oriented developments and multi-story malls, we might ask how development can unfold more deliberately—integrating rather than erasing the histories and social fabrics that make urban life vibrant.

This mindset extends to building methodologies as well. As we strive for ever-greater efficiency, precision, and affordability through prefabrication and industrialized systems, might we also reintroduce the site sensitivity found in vernacular practices? The value of vernacular architecture lies not only in its historical or stylistic expression, but in its principles: responding to context, encouraging bodily-scale interactions, and supporting diverse, everyday activities. Even when a site holds no grand historical narrative, a vernacular approach—thoughtful, adaptable, and rooted in local experience—may better guide the creation of neighborhoods that are engaging, colorful, and genuinely livable.

This article is part of the ArchDaily Topics: Regenerative Design & Rural Ecologies. Every month we explore a topic in-depth through articles, interviews, news, and architecture projects. We invite you to learn more about our ArchDaily Topics. And, as always, at ArchDaily we welcome the contributions of our readers; if you want to submit an article or project, contact us.